In 2004, Congress passed a law that established a moratorium on federal safety regulations for commercial astronauts and space tourists riding to space on new privately owned rockets and spacecraft. The idea was to allow time for new space companies to establish themselves before falling under the burden of regulations, an eventuality that spaceflight startups argued could impede the industry's development.

The moratorium is also known as a "learning period," a term that describes the purpose of the provision. It's supposed to give companies and the Federal Aviation Administration—the agency tasked with overseeing commercial human spaceflight, launch, and re-entry operations—time to learn how to safely fly in space and develop smart regulations, those that make spaceflight safer but don't restrict innovation.

Without action from Congress, by the end of September, the moratorium on human spaceflight regulations will expire. That has many in the commercial space industry concerned.

The House Science Committee is considering a commercial space bill that might extend the learning period, but the content of the bill hasn't been released yet. Rep. Frank Lucas (R-Okla.), chair of the House Science Committee, said one of his priorities in developing the space bill is ensuring a "thoughtful regulatory environment that supports innovation."

Given the hotly partisan tenor of Capitol Hill and a range of other priorities, it's not clear if the bill—whatever it says—can be passed before October 1.

"Things are sort of moving, but... how do you deal with the moratorium? Can you get that by October 1 and get something passed? Is that something everyone can agree to, or is that going to get bogged down? You just don’t know right now, and that’s just a bad place to be," said Allen Cutler, president of the Coalition for Deep Space Exploration, in a panel discussion at the John Glenn Memorial Symposium earlier this month.

Sign a waiver, go to space

The ban on human spaceflight regulations applies only to occupant safety. For every commercial launch, including crew missions, the FAA already has oversight over issues that affect the safety of the general public.

Lawmakers have extended the moratorium twice, most recently in 2015. The commercial space industry is pushing for another extension, arguing that the three companies that have flown commercial human space missions—SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic—haven't matured to the point where passenger safety regulations are needed.

“Allowing the learning period to end this year would lead to regulations that inadvertently freeze development before industry has had time to mature, harming safety and our nation’s competitiveness in the long term," said Karina Drees, president of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation, an industry advocacy group that counts top commercial space companies among its members.

“We want to enable an industry that allows entrepreneurs to flourish [and] that allows new companies to come online with new capabilities, and it’s very difficult to do that if the regulation is already in place," Drees said in a recent House Science Committee hearing.

The industry currently operates under a framework of "informed consent." Commercial astronauts and passengers riding to space with SpaceX, Blue Origin, or Virgin Galactic must sign waivers stating they understand the risks involved in the endeavor. Language in the 2004 law that set up the regulatory moratorium described space transportation as "inherently risky."

“There is a pretty extensive process in place to ensure that the folks that are signing those informed consent waivers know exactly what they’re signing," Drees said.

There have been 10 fully commercial human spaceflight missions to date, three orbital flights with SpaceX, six suborbital launches with Blue Origin, and one flight by Virgin Galactic. These companies' other crew missions that reached space were considered test flights, or in the case of SpaceX, carried professional NASA astronauts.

In this period of regulatory uncertainty, representatives from the major commercial human spaceflight companies are working on non-binding industry standards for passenger safety. Drees suggested that approach was the best way to balance safety considerations with the industry's desire for light-touch regulations.

“The challenge is if we start developing that regulatory environment too soon before we have enough data, before we have enough knowledge of those individual vehicles, there is a long-term safety risk that something could go wrong," Drees told the House Science Committee. "The purpose of continuing to innovate while we develop these standards side by side with the regulator will allow us to have the most safe vehicles on the market in the future.”

Caryn Schenewerk, a space law and policy consultant formerly with SpaceX and Relativity Space, echoed that view in the same House committee hearing. The three companies currently flying people to space on a commercial basis have vastly different vehicle designs, she said. It's not easy, and potentially counterproductive, to write one-size-fits-all regulations for an industry with such a broad range of designs.

"I think it’s an important point that writing a regulation based on a number as small as three is a challenge in and of itself, much less in an industry where you haven’t had a consolidation of design," she said.

Schenewerk said the commercial human spaceflight industry is not operating free of regulation. There are rules about what the human spaceflight providers must tell their passengers about the risks and past mishaps. "The original premise underpinning the learning period still appears solid," she said.

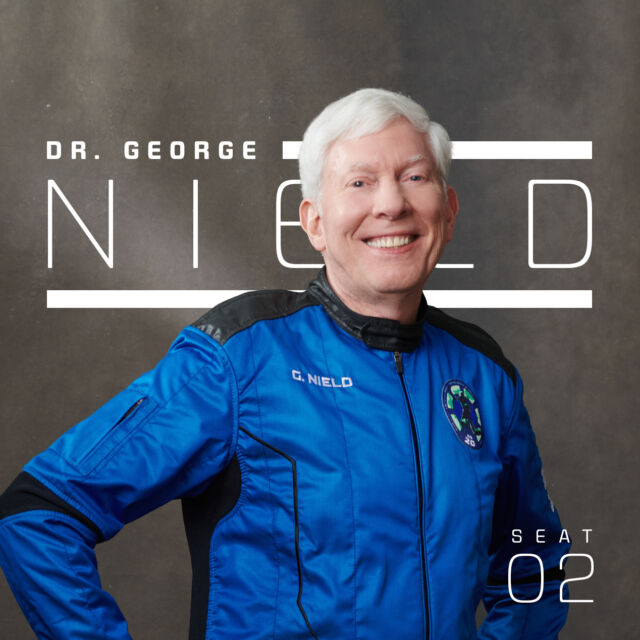

“Anybody who wants to fly on these rockets needs to be thoroughly briefed on all the hazards, all the risks, all the things that could go wrong, that they could be injured or even killed on these flights," said George Nield, a former head of the FAA's Office of Commercial Space Transportation. "Then, if they're still willing to go... they sign the piece of paper and they're allowed to fly."

Nield is in a unique position to understand the informed consent clause, and he is obviously confident in the capabilities of commercial space companies. After retiring from the FAA, he flew to space on Blue Origin's New Shepard rocket in 2022.

The FAA's requirement for informed consent is not very specific, according to Nield. "The responsibility is with the company to know and then to describe the hazards and to ensure that the customers have an opportunity to have the conversation about it, and ask any particular questions they want in order to be prepared to accept that risk.”

What happens if the moratorium expires?

The authors of a study by the RAND Corporation released in April recommended allowing the moratorium to expire this year, despite finding a lack of progress in the industry to set up voluntary standards. But that doesn't necessarily mean regulations should, or will, be introduced immediately.

“I know there are some [in the] industry who think extending the moratorium is very, very important," Nield said. "But frankly, I think their fears are perhaps a bit exaggerated."

"We don’t have a drawer full of regulations ready to go, far from it," said Kelvin Coleman, who now leads the FAA's commercial space office, the division previously headed by Nield.

The FAA "would just like to engage with industry and figure out what the future regulatory framework ought to look like," Nield said. "So, in some sense, there may not be a noticeable change at all, at least in the near term."

Although there are no rules at the ready, regulators at the FAA are preparing for the possibility that the moratorium will end soon.

"We don’t know what will happen here at the end of the fiscal year as the moratorium faces sunset, whether it will sunset or whether it will be extended. We don’t know," Coleman said in May at a meeting of the FAA's commercial space advisory committee. "In the meantime, we thought it best that we not sit on our hands, that we begin to do the necessary work to prepare for the eventuality of regulation of human spaceflight."

The FAA has established a space aerospace rule-making committee to look into different options for regulations, receiving input from industry and "other stakeholders," the FAA says. The committee is expected to work for "the better part of two years" before submitting their recommendations, Coleman said.

Nield wants to see a middle ground between the arguments put forward by the commercial space industry that there's just not enough data to inform smart regulations and those at the other extreme who say private space companies can't be trusted with passenger safety.

“A challenge is to strike the right balance here," he said. "We definitely want industry to have the freedom and flexibility to innovate and to try new ways of doing business, to incorporate new technologies. If you try to tell folks exactly how to do stuff, then you're going to get to limit their freedom to try new things. We don't want to do that. If we try to lock down designs and operational procedures right now, then we're never going to improve our current record of human spaceflight safety."

US human spaceflight missions have, to date, about a 1 percent fatal accident rate (four of around 400 crew missions have resulted in fatalities). That wouldn't be acceptable for commercial air travel.

"So we have a lot of room for improvement, and we need to try new things and figure out what's important, what's not, what works, what doesn’t. But you don't want to lock down the design and say you’ve got to have three parachutes, you’ve got to have wings this big," Nield said. "Instead, let's try and take that up a notch and talk about the processes, dissimilar redundancy, and how can you ensure that you’re going to have breathable air for the folks on-board, and what do you do if there’s an engine failure."

Requiring an in-flight abort or glide capability would make sense in the event of an engine failure, Nield said. That's something commercial space companies have already developed.

Voluntary industry standards could be an intermediate step in the regulatory framework for commercial human spaceflight, but that requires greater transparency between companies that, in the end, are competitors. The companies consider many details about their technology proprietary.

"You don’t have to necessarily make them mandatory," Nield said. "Industry, frankly, is probably the experts in their designs right now. Nobody in the government is going to know better than they do where the vulnerabilities are, where the opportunities are, where the uncertainties are. Let’s help them take on the responsibility of trying new things and learning from our experience in order to continuously improve the safety.”

If the voluntary industry guidelines were published and companies publicly disclosed how they would meet those standards, the human spaceflight providers could use them to show customers and federal regulators that they take safety seriously.

“It ought to be a badge of honor that says, 'Hey, we've gotten together with the government, industry, academia, and come up with what we think are some appropriate common-sense standards and approaches in order to maximize the safety, and we follow those. And here's how we do that,'" Nield said.

What Nield wants to avoid is an environment where a fatal accident triggers a reactive regulation from the FAA. He drew a comparison with the implosion of the commercial Titan submersible last month on an expedition to visit the wreck of the Titanic, killing all five people aboard. While there are major differences in the designs of deep-sea submersibles and space vehicles, both need to withstand extreme environments. And the ticket prices are similar for a wealthy adventurer seeking to travel to space or the deep ocean.

"My fear is that if an accident happens in the near term, then it may cause a lot of interest and attention in the same way that the submersible mishap did recently with the Titan on the way to the Titanic, that people will all of a sudden express shock and dismay—'Oh, my goodness! How did that happen? We have to make sure that that never happens again. FAA, you need to put out some regulations within 60 days,'" Nield said.

"My view of that is, rushed regulations are bad regulations. Let's take our time, but let's get started and see what we can come up with in terms of an overall framework.”

The law that set up the current regulatory regime (or lack thereof) went into effect the same year that Scaled Composites, an outfit in California's Mojave Desert, won a $10 million X Prize by launching the first privately funded piloted spacecraft into suborbital space twice in less than two weeks. The accomplishment led many observers to believe commercial human spaceflight was only a few years away. Virgin Galactic, founded by Richard Branson and using an upsized version of Scaled's suborbital rocket plane, originally aimed to begin flying space tourists in 2007.

But it turned out to be a much longer wait. Virgin Galactic's rocket plane, called SpaceShipTwo, flew its first commercial mission to the edge of space in June after a series of suborbital test flights, including one that carried Branson himself. Jeff Bezos' space company, Blue Origin, flew its first fare-paying passengers on a suborbital spaceflight in 2021, two years ahead of Virgin.

SpaceX's privately owned Dragon crew capsule launched to the International Space Station with two NASA astronauts in 2020. In 2021, SpaceX launched the first fully private orbital spaceflight without the participation of NASA. The Dragon spacecraft can fly missions to the space station lasting up to seven months, while Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin give passengers just a taste of microgravity lasting a few minutes, albeit at a lower cost.

NASA’s role to play

NASA has a stake in whatever happens with the FAA human spaceflight regulations. The space agency spent millions of dollars and took years to certify the safety of SpaceX's Dragon spacecraft for astronauts, and it chairs a flight-readiness review before each NASA crew mission on Dragon flying to the International Space Station.

The time-consuming certification work gives NASA confidence in the safety of Dragon capsules and SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket, clearing the way for those vehicles to ferry government-employed astronauts into orbit.

NASA would eventually like to buy seats for its astronauts on fully commercial missions without extensive NASA oversight, either on launches to suborbital space with companies like Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic, or on a privately managed orbital flight to the ISS or a future commercial space station. That would free up NASA resources spent on certification and oversight for use in other parts of the agency.

For example, Axiom Space has flown two fully commercial private astronaut missions to the ISS, with plans for a third trip in the coming months. Axiom contracted with SpaceX to use its Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon spacecraft and worked with NASA to arrange for access to the space station. But Axiom and SpaceX held the final authority to launch, not NASA.

Those flights, commanded by former NASA astronauts now working for Axiom, flew paying passengers to the space station for stays lasting one to two weeks. Foreign governments like Saudi Arabia and Turkey have also paid for seats on Axiom missions to secure a flight opportunity for their astronauts.

It is conceivable that NASA might want to fly an astronaut or a research scientist (like the payload specialists who flew on space shuttle missions) on a short-duration flight through Axiom or another company. For that to happen, changes are needed in the regulatory regime for US commercial human spaceflight, the space agency says.

"Let's say I wanted to buy one seat on a private astronaut mission for a government astronaut," said Ken Bowersox, NASA's associate administrator for space operations. "I can't do that right now because the missions would require informed consent, and I don't have a way to let a government astronaut do that. But if it was regulated by another government agency, then that might be a possibility."

If commercial spacecraft were regulated in the same way as commercial airplanes, "we could put government astronauts on vehicles like that the way we do on a commercial airliner nowadays," Bowersox said.

In 2020, NASA announced it was interested in flying its employees on suborbital vehicles. Astronauts could fly with Blue Origin or Virgin Galactic for training purposes to prepare for longer-duration stints in orbit, or NASA researchers could tend to their microgravity experiments on a suborbital hop.

Three years later, NASA's suborbital crew program hasn't made much progress. Bowersox told a NASA Advisory Council committee in May that the agency hasn't identified any specific opportunities for an astronaut or government researcher to fly on a suborbital mission, but the program is still alive.

There are several issues at play here. How does NASA account for the safety of commercial rockets and spacecraft without going through an onerous certification effort that expends NASA resources and encumbers private industry? The suborbital rockets flown by Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic are already flying commercial passengers, while NASA worked with SpaceX on certifying the Dragon capsule from the start.

"The agency has a requirement to ensure the safety of our employees when we put them into hazardous situations, including spaceflight," said Phil McAlister, head of NASA's commercial spaceflight division.

Instead of full certification, NASA is taking a different "safety case" approach, where space transportation providers present their safety processes to NASA, which then verifies that those procedures are sound. With Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic, NASA has started "deep dive" assessments of specific technical risks, such as propulsion, parachutes, mechanisms, and operations.

McAlister said the safety analyses should be complete in early 2024. Only then will NASA decide how to proceed with the suborbital crew program. The lessons learned could inform NASA officials on how to evaluate the safety of fully commercial orbital flights.

“The bottom line is without this integrated regulatory regime, we've got some barriers to things that all of us would like to see happen," Bowersox said. "When we have regulation, it can enable things, but the folks on the other side are worried that the regulation could happen too soon and stifle the industry growth. So there's a balance between the two, but there's work going on in this area to try and find a way forward.”