You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A nearly 20-year ban on human spaceflight regulations is set to expire

- Thread starter JournalBot

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Is it literally rocket science when setting a safety standard for rocket science, or just common sense?

Set up a regulatory regime based on targets, defining what must be achieved as a level of residual risk; rather than a rule setting regulator that defines how things must be done and built. Require a safety case with a third party audit, from NASA initially but eventually from other approved bodies that are able to give equivalent independent review.

The recent Titan submarine is an example of the deficiency of relying on just "informed consent".

Set up a regulatory regime based on targets, defining what must be achieved as a level of residual risk; rather than a rule setting regulator that defines how things must be done and built. Require a safety case with a third party audit, from NASA initially but eventually from other approved bodies that are able to give equivalent independent review.

The recent Titan submarine is an example of the deficiency of relying on just "informed consent".

Upvote

105

(124

/

-19)

Why does this sound very much like financial industry decrying effects of regulation on innovation? We all felt how well they innovated their way into 2008 adventure.

Can start with light regulation of the type extensive live telemetry that needs to be handed over in case of any incident. Abort modes for all phases of flight (we learned that it is important with STS so no need to learn it again) and so on.

Can start with light regulation of the type extensive live telemetry that needs to be handed over in case of any incident. Abort modes for all phases of flight (we learned that it is important with STS so no need to learn it again) and so on.

Upvote

125

(135

/

-10)

Upvote

-5

(13

/

-18)

autoteleology

Ars Centurion

I come away from reading this feeling almost as if someone had just explained to me in excruciating detail, using multiple expert sources, that "regulation is when the government does stuff; and there's more regulation the more stuff it does; and if it does a real lot of stuff, it’s communism".

Why is private industry so consumed by paranoia and anxiety on this subject, other than Elon Musk being pathologically rabid about the concept of being told what to do by anyone else? I'm not buying regulation being used so blatantly as a scare word given that there's nothing but vague hypotheticals being gestured at here.

Why is private industry so consumed by paranoia and anxiety on this subject, other than Elon Musk being pathologically rabid about the concept of being told what to do by anyone else? I'm not buying regulation being used so blatantly as a scare word given that there's nothing but vague hypotheticals being gestured at here.

Upvote

97

(131

/

-34)

Only in the US... regulations banning regulations, putting commercial interests over human lives.

Upvote

5

(59

/

-54)

equine_physics

Ars Scholae Palatinae

In the aviation industry there is a saying (or viewpoint) that regulations are written in blood. Airlines and manufacturers may chaff at regulations, but overall, they are meant to protect humans from greed....not just death, but death from greed.

The recent sub accident is one such example, the 737 Max is another. In the former there were no real regulations, in the latter a company was allowed to "look pass" them for cost reasons.

I'm not against any individual attempting to design, build, and launch their own private rocket to get into orbit (or beyond) and I would honestly say that the regulations should be minimal and focused on not harming those around the process. Much of early aviation was built on such acts and pilots did die pushing the boundaries. We cannot nor should not curtail innovation based on an individual's desire. Man or woman want's to build a rocket in a barn and launch it to get to the moon, by all means other then airspace waivers and notification of down stream launch path (and a healthy perimeter). Let them fly.

When you begin to involve passengers, people not directly associated with a project then I feel regulations become important such that the safety of the passenger is considered. SpaceX took the path of multiple tests, test pilots, and continual reviews to help achieve what is today the safest way to get to orbit. Turn your head a little and gaze upon Boeing to see a company that did not.

tldr; we learn from our mistakes. We should not forget them just because we now put "in space" or "under the sea" after the word passenger.

The recent sub accident is one such example, the 737 Max is another. In the former there were no real regulations, in the latter a company was allowed to "look pass" them for cost reasons.

I'm not against any individual attempting to design, build, and launch their own private rocket to get into orbit (or beyond) and I would honestly say that the regulations should be minimal and focused on not harming those around the process. Much of early aviation was built on such acts and pilots did die pushing the boundaries. We cannot nor should not curtail innovation based on an individual's desire. Man or woman want's to build a rocket in a barn and launch it to get to the moon, by all means other then airspace waivers and notification of down stream launch path (and a healthy perimeter). Let them fly.

When you begin to involve passengers, people not directly associated with a project then I feel regulations become important such that the safety of the passenger is considered. SpaceX took the path of multiple tests, test pilots, and continual reviews to help achieve what is today the safest way to get to orbit. Turn your head a little and gaze upon Boeing to see a company that did not.

tldr; we learn from our mistakes. We should not forget them just because we now put "in space" or "under the sea" after the word passenger.

Upvote

169

(171

/

-2)

Post content hidden for low score.

Show…

Post content hidden for low score.

Show…

I am baffled by the tone of this article. It seems to be pretty strongly implying, without actually saying, that this ban on safety regulations is good and it's a problem that it might expire. And yet the only arguments it presents for that position is 'this person who works for one of the companies that might someday be required to value the safety of human beings thinks they shouldn't have to because waves arms dramatically innovation!'.

Upvote

119

(135

/

-16)

Sounds like this ban should expire and the FAA should be able to do its' work. It's going to take them two years to come up with rules anyways which implies a slow and thoughtful process.

Upvote

72

(83

/

-11)

RocketFeathers

Ars Praetorian

Is it too early to crack a joke about needed regulations for deep sea exploration?

Upvote

34

(42

/

-8)

Post content hidden for low score.

Show…

The problem the article is describing is the lack of certainty over whether the moratorium will expire, or be extended. Either way is probably fine for now, imo.

Upvote

11

(12

/

-1)

Calculating risk for novel technologies is really hard--arguably more art than science. I think requiring that any human space access systems be autonomously tested end-to-end a certain number of times before the first humans are on board (for an end-to-end flight) is the safest and most reliable way to properly assess risk. If you can't test autonomously, then human failability must be added to the risk assessment, and there simply isn't enough aggregate data to make such a calculation anything but a guess.Is it literally rocket science when setting a safety standard for rocket science, or just common sense?

Set up a regulatory regime based on targets, defining what must be achieved as a level of residual risk; rather than a rule setting regulator that defines how things must be done and built. Require a safety case with a third party audit, from NASA initially but eventually from other approved bodies that are able to give equivalent independent review.

The recent Titan submarine is an example of the deficiency of relying on just "informed consent".

The upcoming SpaceX Polaris missions seem like the optimal template for gradual risk retirement. Before humans board a Starship for launch, these missions will have proven: Crew Dragon can depressurize and repressurize; humans can safely egress Crew Dragon, move around on a tether, and return to Crew Dragon; Crew Dragon can autonomously dock with Starship; Starship life support works and supports humans for some number of days; that crew Starship can launch and land safely.

Beyond those missions, cargo Starships will have been launching and landing in all sorts of conditions, likely dozens if not hundreds of times. At that point, everything novel will have been tested in situations where risk to life is zero or as close to zero as reasonably possible. In the event of heatshield damage during launch or a problem while in orbit, a flight-proven Crew Dragon can be standing by atop a flight-proven Falcon 9, ready to launch a recovery mission within hours. That's the kind of redundancy and autonomous testing that NASA never even dreamed of, but that might have averted both STS loss-of-life events.

The problem is that for anyone besides SpaceX, there's no flight-proven crew vehicle or flight-proven rocket to provide that safety net. Doing all the other autonomous testing gets you really far however, and maybe NASA could facilitate contracting with SpaceX for contingency operations (with a requirement that any crew-capable space vehicle has a compatible docking port that's been tested in orbit against the ISS or some other compatible vehicle).

Upvote

56

(56

/

0)

The main result of the lack of regulation seems to be that the really dangerously incompetent private space companies (looking at you, Virgin Galactic) take decades to go out of business rather than years. Innovation!

Upvote

26

(34

/

-8)

See this seems like what we are trying to avoid. We don't require that for aircraft - lose all engines over the ocean in a passenger jet and you will ditch. If the overall system is reliable enough, it shouldn't be necessary to specify how that is achieved.

Ditching is an abort mode. It's not a very good one, but it is an abort mode that is rarely used due to reliability of engines so we accept that. As we have seen with 737 max, self-regulation is not a viable option when greed and MBAs are around.

Upvote

62

(64

/

-2)

Without the freedom to innovate (TM), OceanGate would never have been able to produce the Titan submersible. It would be a shame if space flight was similarly hampered. (I don't need a satirical emoticon here I hope.)Only in the US... regulations banning regulations, putting commercial interests over human lives.

"Certification is the crucible within which responsible innovation is possible." -- Patrick Lahey, President, Triton Submarines

Upvote

39

(49

/

-10)

Post content hidden for low score.

Show…

Welsh Dwarf

Seniorius Lurkius

Actually we do require that for aircraft. The blackbox is a regulatory requirement, and even if you don't actually total the aircraft, any near miss requires that the box be sent off for analysis and an investigation opened. Most of these investigations lead to recommendations for the pilotes, the airlines and/or the aircraft manufacturer which are then applied.See this seems like what we are trying to avoid. We don't require that for aircraft - lose all engines over the ocean in a passenger jet and you will ditch. If the overall system is reliable enough, it shouldn't be necessary to specify how that is achieved.

There's a reason that flying is by far the safest way to travel, and it's not market forces.

Upvote

108

(110

/

-2)

fuzzyfuzzyfungus

Ars Tribunus Angusticlavius

It seems like the main thing keeping YOLO-tier human spaceflight viable at the moment is the combination of cost of getting any mass, alive, dead, or killed by the process, off the ground; along with the scarcity of things actually worth having a human do in space.

As long as it's NASA's relatively paranoid prestige/science projects and a handful of edge-of-space tourists the incentives to not let them die line up pretty neatly and everybody's there entirely because they think that space is neat; so it's hard to get too concerned.

Should either of those factors change I'd imagine that space would become a pretty dangerous workplace in short order.

As long as it's NASA's relatively paranoid prestige/science projects and a handful of edge-of-space tourists the incentives to not let them die line up pretty neatly and everybody's there entirely because they think that space is neat; so it's hard to get too concerned.

Should either of those factors change I'd imagine that space would become a pretty dangerous workplace in short order.

Upvote

6

(7

/

-1)

jenesuispasbavard

Seniorius Lurkius

In what universe is a ban on safety regulations a good thing?

Upvote

19

(38

/

-19)

On the one hand, insightful and scientifically supportable safety regulations could actually improve the space tourism industry by avoiding predictable disasters (like the Titan submarine) and improving customer confidence.

On the other hand, I have no doubt that lobbying, regulatory capture, and congressional abuse of power could lead to laws passed specifically to inhibit specific companies.

On the other hand, I have no doubt that lobbying, regulatory capture, and congressional abuse of power could lead to laws passed specifically to inhibit specific companies.

Upvote

28

(31

/

-3)

The billionaire oneIn what universe is a ban on safety regulations a good thing?

Upvote

11

(31

/

-20)

The article makes a reference to 'safety case' but this has a very specific meaning in safety science/engineering. I would suggest the author confirm that this is the intent here or reword if not.

It is certainly possible to write flexible regulations. The EU, for example, commonly writes regulations in the form of non-prescriptive principles. This gives flexibility while still providing a regulatory safeguard. The regulations work hand-in-hand with recognised technical standards. Compliance with a recognised standard provides legal safe harbour (essentially, it means that the organization is considered compliant with the relevant law). Standards are not mandatory and they can be updated over time. Organizations can also use other scientifically valid forms of evidence (including evidence they themselves generate). This is useful when organizations are innovating beyond the scope of any existing technical standards or known science.

Example principles:

It is certainly possible to write flexible regulations. The EU, for example, commonly writes regulations in the form of non-prescriptive principles. This gives flexibility while still providing a regulatory safeguard. The regulations work hand-in-hand with recognised technical standards. Compliance with a recognised standard provides legal safe harbour (essentially, it means that the organization is considered compliant with the relevant law). Standards are not mandatory and they can be updated over time. Organizations can also use other scientifically valid forms of evidence (including evidence they themselves generate). This is useful when organizations are innovating beyond the scope of any existing technical standards or known science.

Example principles:

- Benefit must outweigh the risk

- Priority order for dealing with system hazards:

- Design out,

- Reduce as far as possible,

- Mitigate,

- Inform

Last edited:

Upvote

37

(37

/

0)

autoteleology

Ars Centurion

I can't wait for the people who've killed two dozen astronauts to write the regulations for the people who've killed nobody.

US human spaceflight missions have, to date, about a 1 percent fatal accident rate (four of around 400 crew missions have resulted in fatalities).

It's not as if private spaceflight had half a century of publicly funded experience and technology to copy or anything. How many private manned space flights have there been again?

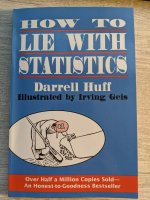

I recommend this book to help you avoid getting dunked on again in the future:

Upvote

50

(52

/

-2)

If anyone has lobbying muscle it's the military industrial complex and look at SpaceX. They have basically crushed all those lobbying competitors because their products actually work and it's very hard to lobby against that.On the other hand, I have no doubt that lobbying, regulatory capture, and congressional abuse of power could lead to laws passed specifically to inhibit specific companies.

Interestingly it seems that lobbying also gets you screwed over as a company. Too many lobbyists and MBAs and you end up like boeing, fighting for your life against Airbus (hardly a shining example of a well run company).

Upvote

15

(15

/

0)

Post content hidden for low score.

Show…

That's generally how safety regulations work. You either learn from past mistakes (yours, or someone else's), or you repeat them. Learning from someone else's mistakes is a lot cheaper and easier.I can't wait for the people who've killed two dozen astronauts to write the regulations for the people who've killed nobody.

Upvote

57

(57

/

0)

Wait what? This is only for human spaceflight, which only affects like four companies. One of which needs a lot more oversight, and with the other three the regulations might help guide them by setting standards for engineering.

All the others are barely getting off the ground with non-human payloads.

All the others are barely getting off the ground with non-human payloads.

Upvote

-1

(6

/

-7)

MacCruiskeen

Ars Praetorian

If you are taking paid passengers essentially as tourists, you are not in the learning/exploratory period. If you are in the learning/experimental stage, you should not be taking paid tourists.

Upvote

32

(41

/

-9)

The debate about specific regulations on human safety, as it goes for many other such "debates", always assumes a few things.

For example, it is assumed that economic progress naturally happens, that sometimes people lose their lives, and that so long as the progress is significant enough, it was worth it.

Economics, and the rules by which we interact within the economy, are all man made. Thus, it is a decision to value X amount of broken eggs/dead humans against Y amount of economic gains (I would point out, gains for who?).

The pretension of economists and their apologists to do this kind of moral geometry is a travesty.

For example, it is assumed that economic progress naturally happens, that sometimes people lose their lives, and that so long as the progress is significant enough, it was worth it.

Economics, and the rules by which we interact within the economy, are all man made. Thus, it is a decision to value X amount of broken eggs/dead humans against Y amount of economic gains (I would point out, gains for who?).

The pretension of economists and their apologists to do this kind of moral geometry is a travesty.

Upvote

-9

(7

/

-16)

First of all, most commercial passenger plans flying flights across oceans are pretty well all twin engined, and subject to ETOPS in order to be allowed to do so.See this seems like what we are trying to avoid. We don't require that for aircraft - lose all engines over the ocean in a passenger jet and you will ditch. If the overall system is reliable enough, it shouldn't be necessary to specify how that is achieved.

ETOPS (/iːˈtɒps/) is an acronym for Extended-range Twin-engine Operations Performance Standards—a special part of flight rules for one-engine-inoperative flight conditions. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) coined the acronym for twin-engine aircraft operation in airspace further than one hour from a diversion airport at the one-engine-inoperative cruise speed, over water or remote lands, or on routes previously restricted to three- and four-engine aircraft.[1]

And secondly, after Malaysian Airlines flight 370, a lot of thought was put into making sure that aircraft simply couldn't disappear from communications like that flight did. EG:

In 2016, the ICAO adopted a standard that, by November 2018, all aircraft over open ocean report their position every 15 minutes.[370] In March, the ICAO approved an amendment to the Chicago Convention requiring new aircraft manufactured after 1 January 2021 to have autonomous tracking devices which could send location information at least once per minute in distress circumstances

So IMHO we are regulating how safety is implemented on aircraft.

Upvote

46

(46

/

0)

I'm usually a big fan of Ars' editorial slant, and I absolutely love the focus and deep dives on space flight, but there's always been a glaring undercurrent of...fanboyism in relation to private entities.I am baffled by the tone of this article. It seems to be pretty strongly implying, without actually saying, that this ban on safety regulations is good and it's a problem that it might expire. And yet the only arguments it presents for that position is 'this person who works for one of the companies that might someday be required to value the safety of human beings thinks they shouldn't have to because waves arms dramatically innovation!'.

SpaceX has done incredible things, but that doesn't mean I want Musk's Gulch (XGulch?).

Upvote

12

(25

/

-13)

I agree that the private space industry doesn’t need passenger safety regulations until they start offering their services to private passengers for payment.

Oh, they already do? Never mind.

Oh, they already do? Never mind.

Upvote

16

(22

/

-6)

The irony being that OceabGate could have submitted their design for certification by an industry body setup by the companies involved in deep sea exploration, but chose not to. What we've been hearing since the incident is that certification is that such certification would most likely have been denied as numerous knowledgeable individuals in the field had concerns over the design and materials.Without the freedom to innovate (TM), OceanGate would never have been able to produce the Titan submersible. It would be a shame if space flight was similarly hampered. (I don't need a satirical emoticon here I hope.)

"Certification is the crucible within which responsible innovation is possible." -- Patrick Lahey, President, Triton Submarines

Back to the space flight situation: at a minimum, it would seem reasonable for the FAA and NASA to work with the various companies to formulate a set of best-practice principles and guidelines on design considerations, testing, systems redundancy, etc. That doesn't have to specific hardware specifics, but it would at least bring together all the "lessons learned" from their cumulative experience.

Upvote

31

(32

/

-1)

I have no idea what sort of regulation is being held off by this moratorium, but I'd be interested to see how it would address the difference in approach of SpaceX compared to Virgin Galactic vis a vis automation. SpaceX seems to be following the approach of automation is good, while Virgin Galactic maintains a virtually entirely manual, hands on approach. I'm not in a position to judge the engineering merits of either approach, but it seems that fully relying on pilots is an issue in itself.

Upvote

3

(3

/

0)

I can't wait for the people who've killed two dozen astronauts to write the regulations for the people who've killed nobody.

Three die in Branson's space tourism rocket tests

Three people have been killed in an explosion during a test of rocket systems to be used in Richard Branson's proposed space tourism ventures, according to officials and reports today.

VSS Enterprise crash - Wikipedia

Upvote

22

(24

/

-2)

And the reason that ditching over the ocean is possible is because there's requirements for preparedness in case of loss of all engines, designs to be able to control the plane, etc. There's SO many rules and regulations for aircraft that even if they lose all their engines there still have to be MORE backup systems to ensure basic flight controls, radios, etc. continue functioning for a minimum amount of time, giving them an opportunity to save it with a controlled ditching/landing.See this seems like what we are trying to avoid. We don't require that for aircraft - lose all engines over the ocean in a passenger jet and you will ditch. If the overall system is reliable enough, it shouldn't be necessary to specify how that is achieved.

Suppose there were no regulations on redundancy and so when the engines stopped all the instruments, hydraulics, radios, and flight control computers just cut off abruptly and everything is fly-by-wire suddenly they can't control the airplane's angles/altitudes/pitch and it just does uncontrolled loops like a paper plane before slamming into the water at high speed......how do you suppose that would go for the passengers? Oh, and those emergency locator beacons, life rafts, flotation devices, etc are expensive - it'd be a lot cheaper to not have them...good luck getting found or rescued before you drown if you survive.

Every aviation regulation is written in the blood, usually the blood of hundreds of people who died horribly because there wasn't a rule saying they had to be able to handle X emergency, or didn't plan for Y redundancy.

Upvote

28

(30

/

-2)